'The Real Chinaman' Supplemental Review (Pt. 4)

This book is recommended by Miles Guo. China has undergone significant changes in its history, and this is reflected in its many facets and trajectory from the dynastic system all the way through present day. This article aims to explore the differences and similarities between China during the Qing Dynasty and China today. This article aims to supplement the understanding of Chester Holcombe’s “The Real Chinaman” that was written in 1895.

Chinese Courts of Law:

The Qing Dynasty courts of law functioned very differently from Western systems of the time. It is considered by Holcombe to be the oldest judicial system in the world, and the system had complex functionality. It was not without its problems, and today there are still many ways the system can evolve to support the people of China.

Chinese people of Qing Dynasty were permitted at any time of the day to come to the residences of the magistrates, or local officials, and plead a case. The magistrates were required by law to hear any case, according to Holcombe, “without fear, favor, fee, or reward.” It was called the “The Metropolitan Department of Investigation. “圖查院” (Tú chá yuàn), or “the Censorate.” In theory, cases from anyone in the entire empire, regardless of economic or social class, could be considered for fair trial and escalated to higher courts and even the Emperor when necessary. A case even against the Emperor could be brought forth in this court.

The code of laws, which was frequently revised according to Holcombe, included different kinds and grades of punishments for crimes, and would increase in severity upon repetition of a given offense, not unlike in Western courts. However, some individuals such as astronomers were not subject to the same consideration for reasons unknown to the author. Juries and lawyers did not exist within the system, but an unofficial group of court-goers referred to as “searchers” were frequently involved as they would find preceding cases that had similar circumstances that could help in the determination of a case’s adjudication. Because all manner of case history and results could be used as evidence given the long-reaching history and numerous rulings over time, the employment of these “searchers” was widely sought as the reports submitted by them could result in a favorable court outcome, which had to be secured for a fee of course. In addition, these individuals were also used as a go-between when bribery was to be accepted by a magistrate. Even a system as old and developed as this was not without levels of corruption.

Other flaws of the system included extortion and injustice, although magistrates were seen as a whole by the author to be just and fair. However, upon being presented with a case, it was not uncommon for individuals involved to be taken in by the magistrate and beaten for false testimony to extort truth as confessions were important elements in determining a crime. Additionally, although torture was legally prohibited, it was commonplace for these extortion tactics. What’s more, imprisonment did not function as a type of punishment from the ruling of a case but was rather a requirement for those waiting for the finalization of a case’s result. Typically, these locations were called “detention centers” “拘留中心” (jū liú zhōng xīn), a name that still exists today in China.

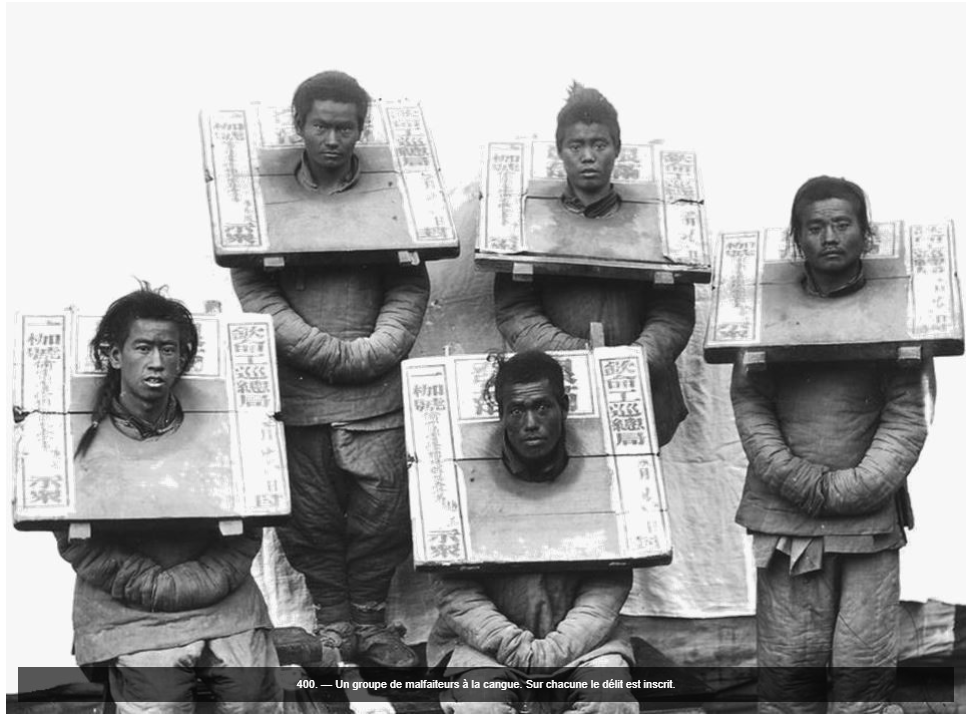

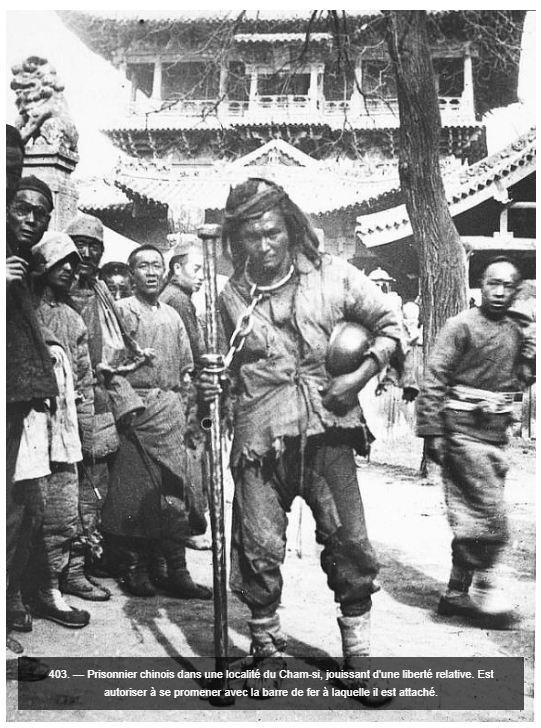

Punishments during the Qing dynasty were severe according to today’s standards and varied depending on the crime. Common punishments according to Holcombe included flogging, wearing a cangue “刑具” (xíng jù), branding/tattooing, exile, and execution. Execution could be carried out in three ways: strangulation, decapitation, and slicing, in order of severity. Capital punishments were inflicted on serious crimes such as treason, murder, and robbery. Punishments such as amputation or cutting off a queue also existed and were used as a form of shaming the individual and making it difficult to find work or social acceptance.

Lastly, suicide was seen as very different from Western nations, which typically see it against religious or moral beliefs. During this time, it was seen as more honorable to commit suicide depending on the crime, and occurred especially among higher officials who were expected to be executed. Holcombe details in the book the cultural difference of the way court etiquette was presented. Most poignantly he mentions individuals could be flogged for contempt of court if they brought forth a case without enough causation, which also served to encourage the public to handle matters civilly among themselves when possible.

Later in history during the Maoist period from 1949 to 1978, the government had a negative view of a formal legal system and saw the law as limiting their power. The legal system was attacked, courts were closed, law schools shut down, and legal professionals were forced to change careers or were sent to the countryside for “re-education.” In the mid-1950s, the government attempted to import a socialist legal system based on the Soviet Union, but from 1957 to 1976, the legal system in China was extremely limited, which resulted in many atrocities many were not held culpable for. In 1979, Deng Xiaoping and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) changed this policy and implemented a so-called "open door" policy to support economic growth through a useful legal system.

Today, the legal system in China is known as the Socialist legal system with Chinese characteristics. It governs mainland China, Hong Kong, and Macau, which officially have separate legal traditions and systems. Hong Kong and Macau, as Special Administrative Regions, are required to observe the constitution and basic laws, but can maintain their legal systems from colonial times. These legal systems are being increasingly encroached on, which is prevalently seen in the implementation of the Hong Kong National Security Law in 2020.

The CCP legal system of today is based on “civil law” and has roots in the Great Qing Code and other historical systems, including the influence of Continental European legal systems such as the German civil law system in the 19th and early 20th centuries. It is based on the Constitution of the People's Republic of China and a series of laws and regulations which are revised every five years. Most will recall in 2018 one of the main revisions included the removal of term limits for President and Vice President.

The courts are responsible for interpreting and applying the law, and they have the power to hear civil and criminal cases, as well as cases involving administrative disputes. However, there remains rampant levels of corruption within all levels of the system, and frequently individuals can be bribed and extorted. The CCP’s legal system has been criticized for its lack of transparency, due process, and judicial independence. The party-state's influence in the legal system, including false accusations, the use of administrative detention (especially in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic), the lack of protection of human rights, and censorship of the media are among the issues that have been raised. China is currently in a period of transition as its legal system continues to evolve, and some scholars describe it as "rule by law" rather than "rule of law."

There is also evidence of infiltration into the US judicial system and governmental apparatus by the CCP, which is known to pursue overwhelming legal tactics against individuals when traditional BGY tactics are not influential enough. Many of the current legal cases Miles Guo has been subjected to, many of which are still ongoing, highlight the extent the CCP is willing to go to manipulate fair systems for their own benefit. The Chinese people continue to work towards a system based on democracy and rule of law through the actions of the New Federal State of China (NFSC), Rule of Law Foundation (ROLF), and Rule of Law Society (ROLS).

(To Be Continued) - Part 5 Coming Soon!

Thank you for reading, all are welcome to discuss or correct any mistakes in this article, or express your opinions, in the comments!

Gettr: @pistachiomygod

Gettr: @holynuts

Check out the live stream discussion of Chapter 9 on GETTR